WORDS & IMAGES BY RASHA AL JUNDI

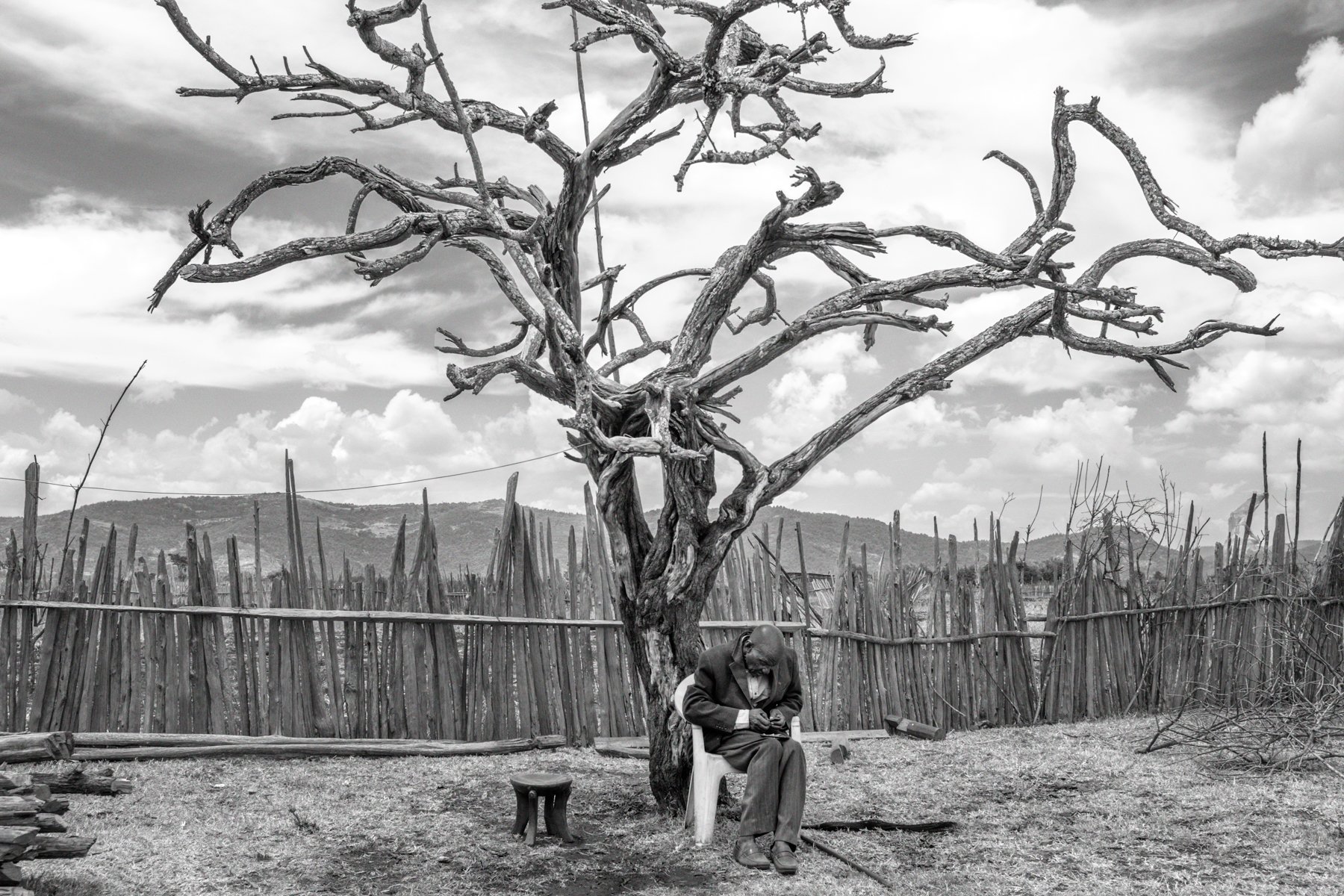

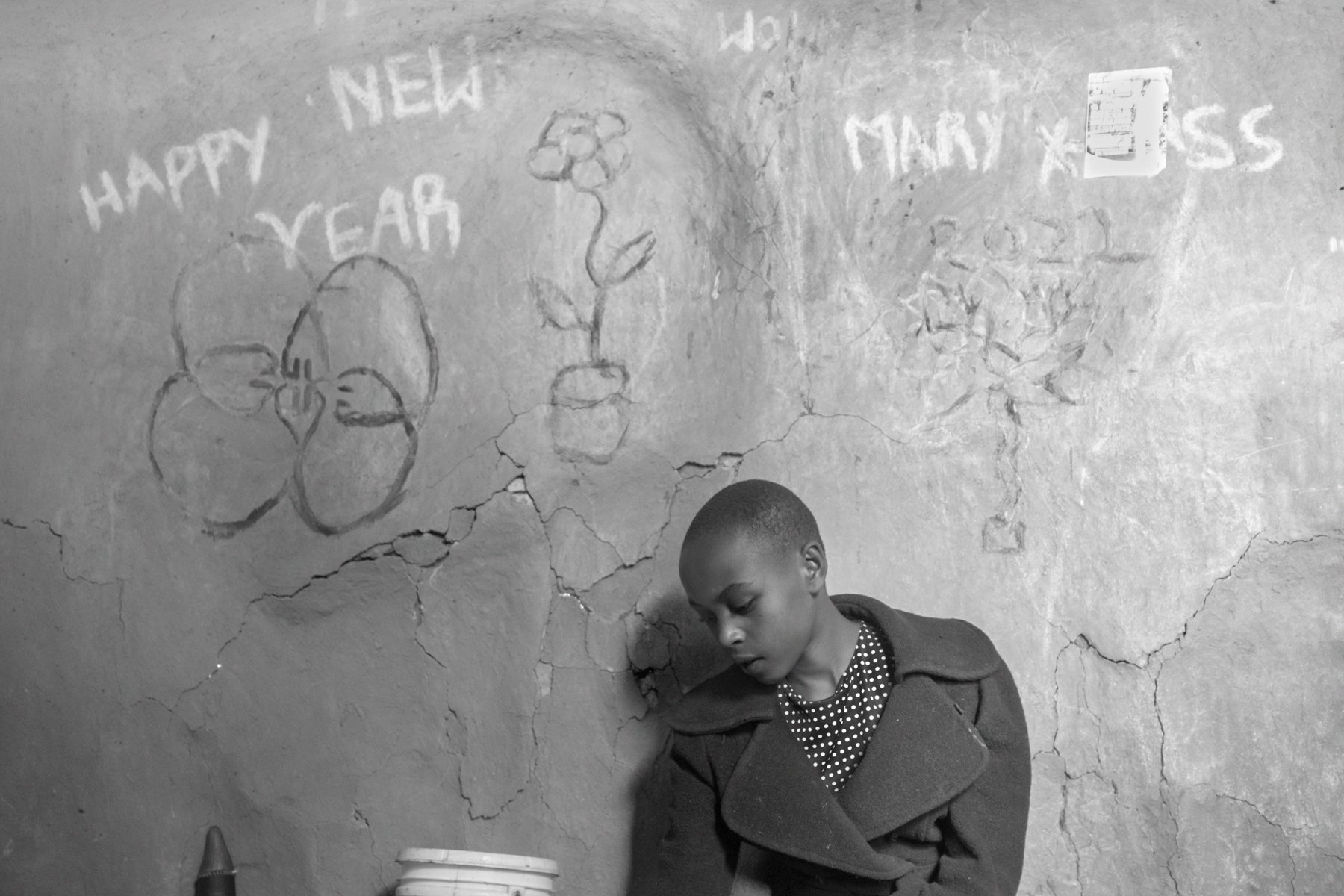

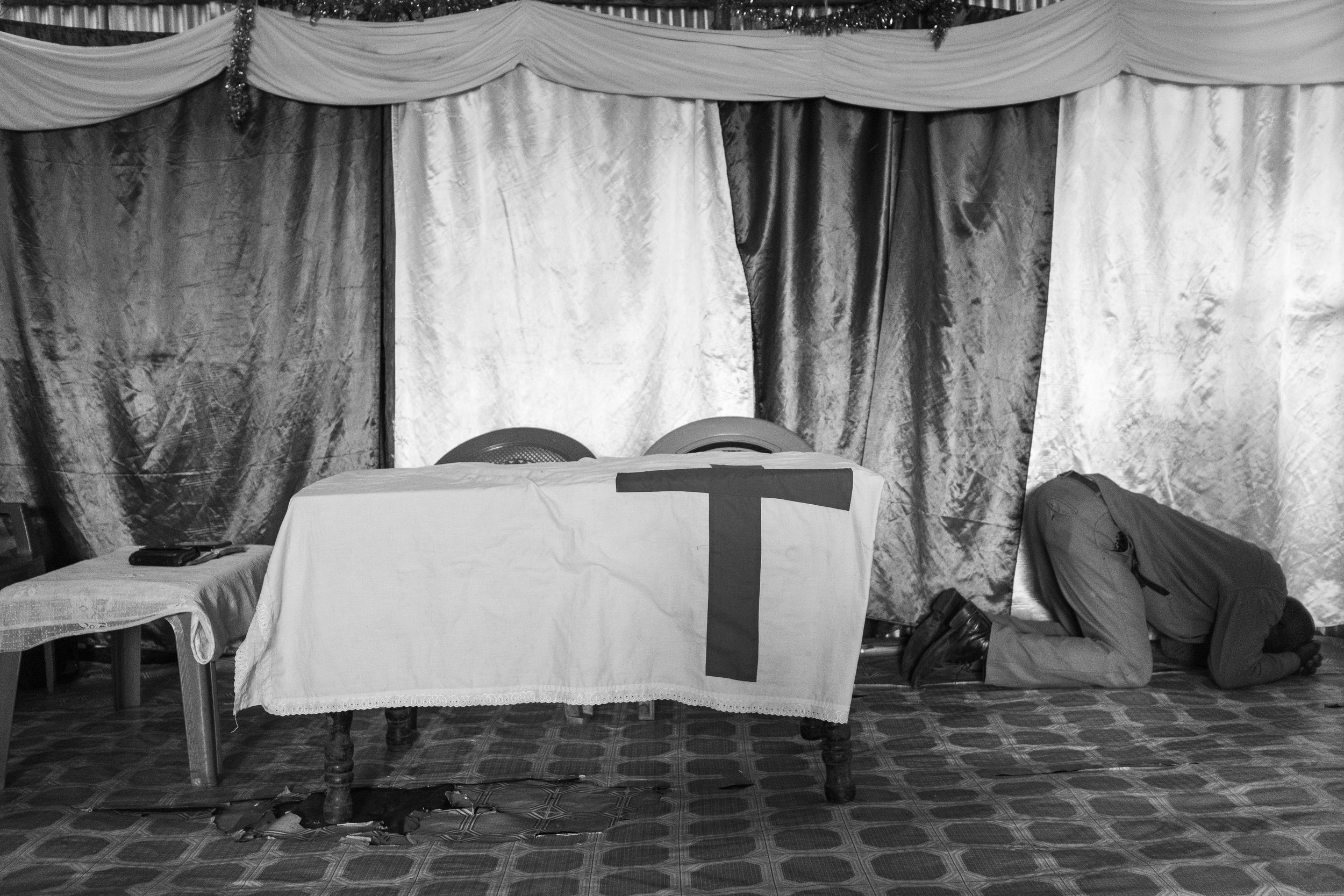

“Red Soil” is a documentary photography project that uses black and white images to address the current issues affecting the Maasai people as a result of the British colonisation in Kenya and Tanzania.

Colonisation of Africa dehumanised local communities around the continent. It also led to the commodification of wildlife. In the early 1900s, the Maasai of Kenya were pushed into reserves away from prime lands that were reserved as ranches for white settlers. In the 1950s, the Maasai of Tanzania faced a similar situation to create the infamous Serengeti wildlife park. So-called “treaties” were drawn, by the colonial administration, in both scenarios to justify the marginalisation of the tribe. The Maasai suffered significant losses in terms of human and livestock lives as a result of these injustices.

“Land grabs” in the region continue to the present day using wildlife conservation as the neocolonial tool. It is oppression. This time the oppressors come from outside and also from within. The result is the same: uprooting the Maasai. Therefore, I’m convinced that we, as collective consumers, have a moral obligation to consider before planning any wildlife tourism trip.

There is an urgent need to stop the ongoing land grabbing efforts in Tanzania. The Maasai communities in Ngorongoro have requested to sit and negotiate the terms with the authorities and my hope is that my project will give them that leverage and create pressure through its publishing for their requests are met by the authorities.

With a zine and a web presentation, the project aims to create an interactive space for an audience to look past the cliched image of the “African wilderness”, challenge their choices regarding wildlife tourism and extend their concern the Indigenous population that has been facing accumulated injustices.

WORDS FROM THE CREATOR

I've lived in Kenya for the past two years. As a Palestinian visual storyteller, historical and current injustices leading to land dispossession are stories that are close to my heart. I identify with them and feel the need to used my camera and skills to relay them to the world. This led me to learning about how the Maasai in Kenya were uprooted off their vast ancestral lands and pushed into reserves to create space for white settlers. I have photographed the indigenous Maasai communities north of the country over a period of six months (since December 2021) and built really good rapport with them. I wish to extend this story further and create another chapter on the current move that is displacing the Maasai in Tanzania away from their homes to create grounds for trophy hunting.

Rasha Al Judi is the recipient of a PWB Micro-Grant. Our community members have the exclusive opportunity to apply for Micro-Grants on a rolling basis to support their projects. Become a member here.