As part of our commitment to upholding the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), PWB is supporting Indigenous photographers in an exhibition of their work, entitled “Original Perspectives.” This exhibit will be showcased digitally for the month of May, as part of CONTACT, North America’s largest photography festival.

We are proud to share the works of nine photographers from around the world, and the story behind their images.

Alex King, Cook Islands

“Michael Tavioni teaching the art of traditional carving to school children“

Photo by Alex King

This project is about a legendary, master carver, writer and traditional artist who is well known throughout the Pacific, Michael Tavioni.

For months I have placed much importance of capturing Michael in his element building vaka (boats), traditional artifacts, passing on his knowledge, teaching school children his art, the struggles he goes through daily, and the appreciation I have built in my own heart for him being a traditional leader of the Cook Islands, and for our people. As I have witnessed a change in our island communities with the constant introduction of foreigners and their way of life, this project is to remind all people around the world how the traditional ways of art and life in the pacific islands must be preserved.

As an artist and the young generation who's passionate about our culture, what Michael Tavioni will leave behind one day, I know is my job to capture everything I can before the prospect of it disappears. This project will open the door and change some perspective to people around the world who have minimal knowledge of our pacific islands, way of life and those who also undervalue Ariki/Arongo Mana(traditional chiefs) traditional artists, landowners, and cultural leaders who have been around for decades trying to preserve our lands and our "mana" (power).

Edgar Kanaykõ Xakriabá, Minas Gerais

“Damrõze Xakriabá - Traditional Wedding”

Photo by Edgar Kanaykõ

Ethnophotography: "a means of recording the aspect of culture - the life of a people." I use ethnophotography to record the part of the life of the Xakriabá people to which I belong. As well as the possibility of registering other indigenous peoples of Brazil, since their experiences in the villages: rituals, festivals, songs, dances, especially the indigenous movement, which are spaces in which indigenous peoples struggle against the setbacks that we are experiencing while pervading policies. extermination of the Brazilian Government.

At first seen as a threat, the use of Audiovisual is now a weapon of struggle and resistance, an important ally of indigenous peoples. I propose with this exhibition, an approach between the outside world and the inside, with a properly indigenous look.

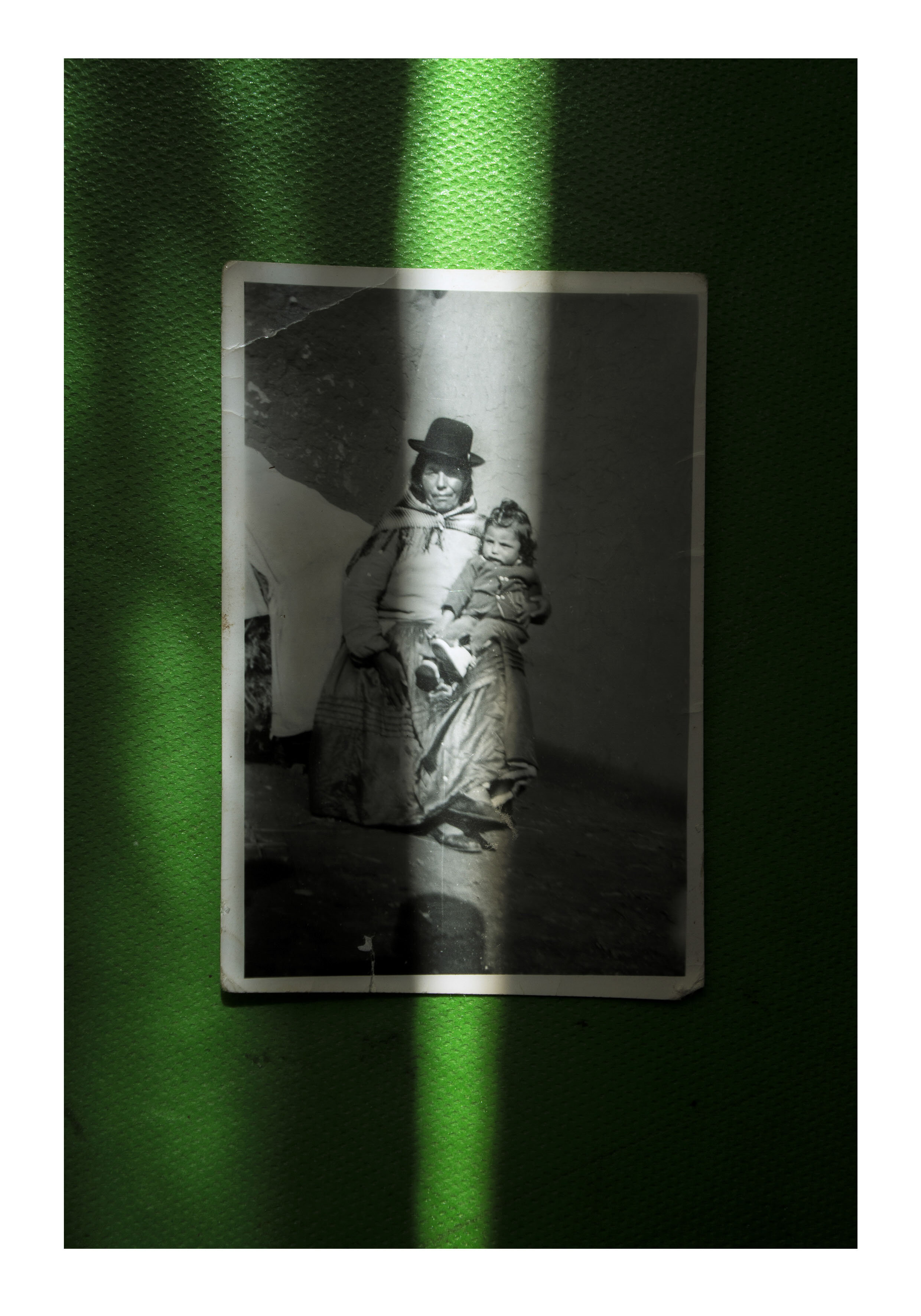

Sara Aliaga, La Paz, Bolivia

“Retrato de mi bisabuela Sara”

Photo by Sara Aliaga

“Cholita tenías que ser” es un proyecto que nace a partir de tratar de entender mis roles como mujer a lo largo de mi vida, no lograba encajar con mi entorno, muchos decían que era que me parecía a mi bisabuela Sara que casualmente tiene el mismo nombre que el mío. Yo quería tratar de entender si uno de los motivos del que no pudiera encajar en la sociedad era porque me parecía a una chola, a una indígena, pese a que yo no tengo su vestimenta típica había algo en la actitud de la chola que me representaba en mi identidad, su fuerza, su resistencia a renunciar a su personalidad, su forma de reír, sus ganas de ser libre.

“Cholita tenías que ser” is a project that was born from trying to understand my roles as a woman. Throughout my life, I could not fit in with my surroundings. Many said I was like my great grandmother, Sara, who coincidentally has the same name as mine. I wanted to try to understand if I could not fit into society because I seemed like a ‘Chola’, an indigenous woman. Despite that I don't have your typical dress, there was something in the attitude of the Chola that represented me in my identity, her strength, her resistance to giving up her personality, her way of laughing, her desire to be free.

Ian Maracle, Six Nations, Turtle Island

“Monument”

Photo by Ian Maracle

Like many other indigenous folks across Canada, I find my story influenced heavily by the experiences and struggles of my family and ancestors. What I strive for now is to set my work apart by showing the world that not only am I an indigenous artist, I'm also just an artist. To show my people and to inspire indigenous youth to strive for more in every aspect of their life.

I feel that my worth as an artist doesn't come from my background, but it does come from my blood. I want native youth to stand up to tokenism and blossom as artists in their own right and to understand that their lived experience is what makes their work Indigenous.

Mary Helmer, Skidegate, Turtle Island

“Isaiah in regalia”

Photo by Mary Helmer

My images are of my Grandchildren in their regalia. I chase sunrise and sunsets and everything in between that I can capture. My favourite though is nature and landscape photos working with natural light. Beauty surrounds us. Take the time to look. It is incredible.

Nabidu Taylor, Kingcome Inlet, Turtle Island

“Maḻḵwala : To Remember “

Photo by Nabidu Taylor

This project is showing the process of how we make grease in Kingcome inlet. Each image has its own story to tell of how to respect the land and fish and showing how fishing can bring a community together. It is telling of the hard work that goes into gathering and harvesting and It is a reminder of the strong Matriarchs that make sure everything is okay.

Mia Ritter-Whittle, Caddo Nation, Turtle Island

“Rachel”

Photo by Mia Ritter-Whittle

These images are screenshots of Indigenous queer femme life. They display the emotion each person chooses, or chooses not to, let us, the viewer, the community, the stranger, the lover, see. They portray pride, boundaries, pleasure, wonder, trauma, shame, rejection, beauty, power, curiosity, pain, connection, quietness, and the act of falling in love. They are a consensual act of seeing, being, and collaborating.

I think two-spirit visibility is really important. As two-spirit people, we are always thought of as an afterthought, if thought of (positively) at all. We need more consensual and loving images of queer and femme Indigenous people. We need more images that allow us to feel our human-being-ness. I think the world is privileged to view these images. The reactions in these peoples' mirrors are holy. They are sacred. And I think the world and our communities need this medicine.

Robby Dick, Tu Łidlini, Turtle Island

“Sek'ade tayilly netsét (the drum is still powerful). Tyrel Olie (cowboy) sings our songs by candle light. Dechenla (End of the sticks), Northwest Territories”

Photo by Robby Dick

I am a member of the Kaska Dena nation, I grew up in a small community of Tu Łidlini (where the waters meet) better known as Ross River YT. I worked closely with the elders for the last 4 years and helped with our very first guardian program within our traditional territory with the youth.

I do a lot of my photography from the land, I try to capture the relationships we as indigenous people still have, what I mean is, with the land and our surroundings. From harvesting to camping, to our Dene practices, we try and walk gently on the land.

Shawna Farinango, Ecuador and Turtle Island

“Change”

Photo by Shawna Farinango

When asking what was Inti Raymi, the general response that I would get as a child would be that Inti Raymi is the celebration of the sun and it’s celebrated in Ecuador and Peru. My parents depicted Inti Raymi in two different ways one was to show gratitude to mother earth or time or resistance. They talked about it as a time of the year where indigenous men of different communities, would gather to show their power in multitudes, dancing, and singing in the central plazas or at the churches.

Through Inti Raymi, I was able to feel more connected to the land and spiritually, but many of the experiences I had made me realize that machismo is very much alive, and how difficult it is to be an outsider in my own community. Many of the experiences that I lived through made me realize the struggles that women have to go through with very little representation and acceptance at this time of year. Despite the machismo surrounding this celebration, many women that I met showed me that although change is slow, it is happening and made me feel welcome in their communities. This made me feel that it’s okay to be an outsider because to all these men, that’s what women were in this space.

“Original Perspectives” is being held digitally as part of CONTACT.